What did we learn from the mini budget, as yields rose and liquidity fell? And what should schemes consider next?

Following a mini budget aimed to support the UK economy on 23 September 2022, gilt markets reacted badly to the proposals, and many pension schemes saw significant impacts on their matching investments. So what did trustees do to support their schemes, what have we learnt, and is there any good news?

The market backdrop

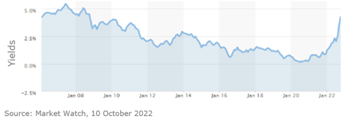

With gilt yields falling under the weight of QE since the credit crunch in 2008, and the monetary response to the Covid-19 pandemic, pension schemes have seen the present value of their liabilities increase much faster than their asset values. This has encouraged schemes who could afford to do so to invest in Liability Driven Investments (LDI).

These investments, sold as assets to match the movement in liabilities, often contained leverage, which increased the level of “protection” for each £1 invested. For those who could afford to invest in LDI, the support it gave as yields continued to fall to 0.1% in July 2020, protected many companies from needing to input significant sums of cash

at potentially difficult times.

So what went wrong? Many schemes holding LDI had considered what a rise in rates might do based on historic movements, and many had put in place structures to support cash collateral calls if rates rose by, say, one percent over a number of months. However, since late last year there has been pressure on yields with with the Bank of England progressively increasing the base rate, and on Friday 23 September 2022, as a new Prime Minister and Chancellor announced a mini budget aimed to support the UK economy, bond markets took a negative view of these proposals. The mini budget announced significant tax cuts, the likes of which we’ve not seen since the 1980s, at a time when the economy looked fragile. This, coupled with the implied increase in government borrowing to fund the budget, caused gilt yields to rise steeply (to over 4.5%) as gilts were sold off. This resulted in significantly more cash to be called for than expected by schemes running LDI strategies. Ultimately, the Bank of England had to step in to support the orderly functioning of the gilt market as liquidity had dried up, supporting pension schemes even though that was not the goal of the Bank.

The support of the Bank, however, was only a pause for pension schemes, and still meant many schemes needed to find significant cash to maintain their LDI positions, or risk losing them at a time when, if rates fell again, they would be exposed to the losses they were attempting to avoid in the first place.

What did we do

Ultimately, when a scheme is required to meet collateral calls, our first step is to ensure there are assets to do so. These may be cash, or more liquid investments such as short-dated credit funds, but for most schemes we have a clear collateral waterfall setting out where to take assets from to meet the collateral call. The process is not automated, as it is important to consider – particularly in changing market environments like we saw – if the plan put in place still makes sense, or if other options are more appropriate – such as selling an overweight equity fund. Being able to have these discussions, make decisions and move quickly has been vital.

Our sole trustee clients in particular have benefited from our depth of experience in markets and complex products, and our approach of running pensions like a business. Robust governance structures have meant focused discussions, decisions based on fact and actions to give schemes the best possible outcomes even where time was short.

There are two key challenges we are aware schemes in the wider market have experienced which has impacted their outcomes.

The first and most important is liquidity. Assets that many pension schemes held as part of their collateral waterfall have either experienced discounts from usual pricing, or delays to accessing the investments. Given the short timescales required and the volume of cash that has been called, managing this has been difficult for many, with some selling assets at discounts and others needing to reduce their LDI positions as they couldn’t get cash on time.

This brings us to the second challenge, governance. Getting trustees together to make decisions on such short notice, particularly when they have other commitments or aren’t full time trustees, can be difficult. Without this, even with good planning and collateral waterfalls, schemes may not have achieved the best outcomes they could have.

What did we learn

The process has ultimately been a significant test on a system which has forgotten many of the lessons of 2008, most notably what liquidity is like when there is little to no liquidity and how important good governance and effective decision making is in time of stress! For trustees, the appropriate testing of our schemes and the assumptions we all hold, robust challenge to our consultants, and reviewing our processes is something that can easily get lost unless we prioritise it.

So the big question, does that mean LDI should not be used in the future, particularly when leverage levels appear to be reducing and physical gilts held up much better? Some would suggest the challenges around LDI mean it has never been the right answer for pension schemes – which when we consider the Bank of England needing to step in may not be unfounded. However, the protection it has afforded many sponsors through several valuation cycles may suggest that LDI does have a place, but we should challenge the broader system many schemes have around pensions management.

New opportunities?

So with all the challenges we have seen in the press since the mini budget, is there any positive news? Yes. The good news is, for most pension schemes, with yields still around 2% higher than 30 June 2022, most schemes will have seen significant improvements in funding. Even those who were fully funded and hedged on a technical provisions basis should still have seen improvements compared to their long-term targets.

Across our schemes we have seen a number move to fully funded on a buyout basis, and so it has been very important for us to capture this improvement where possible, taking out risk and moving to more buy-out ready strategies. This will be key given the capacity in the buyout market and the number of schemes that will now be at or closer to buyout.

Even those who have just seen significant improvements in technical provisions funding, if they can lock this in, it will help reduce risk and protecting funding levels if yields reverse. This will be particularly key for schemes with a H1 2022 Actuarial Valuation, who may have been in deficit at that date, and look to start negotiating contributions. By locking in current positions, the trustees will improve the scheme position and the sponsor will also benefit from a lower risk, lower deficit scheme. Win-win.

Making changes to strategies to lock in these gains however does not come without challenge. The liquidity issues we have mentioned, along with moving quickly to capture gains, without having a knee-jerk reaction and selling out of growth assets at any cost is a balancing act. Many managers, particularly of less-liquid funds are trading at discount, or imposing delays to trading/settlement, meaning understanding of each scheme’s circumstance, how it can benefit and the most appropriate approach is vital to getting the best outcome. But are there opportunities? Yes. For those who have the information and can act in a robust manner, you may find yourselves in a better reported position that before the mini-budget.

To discuss the above, or any other aspect we can help with, please get in touch by emailing sarah.leslie@ndapt.com